Zohran Mamdani is stepping up his Jewish outreach, as he holds private meetings with rabbis and other leaders across New York City who oppose his stance on Israel.

Oct. 16, 2025Updated 8:20 a.m. ET

The tension spilled out of the synagogue onto the sidewalk.

Zohran Mamdani, the Democratic nominee for mayor of New York City, was walking into what should have been friendly territory: a liberal Reform congregation in Park Slope, a neighborhood in Brooklyn synonymous with progressive politics.

But from the moment he arrived last Sunday afternoon, it was clear that even here, Mr. Mamdani would face skepticism and anxiety about some of his foundational beliefs.

A group of protesters waving Israeli flags stood on the steps of the main sanctuary of the synagogue, Congregation Beth Elohim, chanting “shame.” And inside, at a closed-door meeting, synagogue leaders posed questions to Mr. Mamdani reflecting the fears that have grown among some in the Jewish community in the two years since the Oct. 7 attacks in Israel.

“Many of us are afraid that your words and your silences — even though I do not believe that you intend this — will be read as permission by people on the left who want to do us harm, and that someone’s going to try to come into this building to kill us,” said Rabbi Rachel Timoner, who leads Congregation Beth Elohim, according to several attendees.

Mr. Mamdani, who would be New York’s first Muslim mayor, tried to reassure attendees of his commitment to protecting and celebrating the Jewish community, and said that views on Israel would not amount to a litmus test to serve in his administration.

“I am not a Zionist, and I’m also not looking to create a City Hall or city in my image,” he told the 380 members who attended the hourlong gathering, some of whom greeted him with cheers and applause. “I do not want any Jewish New Yorker to think that their safety, their belonging, their identity as a New Yorker, is dependent upon what they think about Zionism.”

The event marked Mr. Mamdani’s latest effort to accelerate his Jewish outreach, as he holds private meetings with rabbis and other leaders across New York City in an effort to engage a community that has been fiercely divided over his bid.

His meetings have spanned a diverse swath of religious life, including gatherings with leaders from the Hasidic communities in Brooklyn, reform rabbis from Manhattan and progressive “God-optional” congregations.

The conversations amount to a testing of the waters on both sides of what has been a fraught relationship between Mr. Mamdani and many Jewish leaders who have struggled to stomach a candidate offering the most outspoken opposition to Israel and its government of any major mayoral nominee in living memory.

They are also a tacit recognition from parts of the Jewish institutional world that he is the overwhelming favorite to win.

But making headway has not been easy for Mr. Mamdani.

At the events, he has promised to combat rising antisemitism, faced questions about whether he sufficiently distanced himself from the phrase “globalize the intifada,” which has been seen as a call to violence against Jews, and suggested that Israeli restaurants and synagogues are not appropriate targets for protest against the Israeli government.

But he has refused to compromise on his opposition to Israel as a Jewish state.

When questioned on Sunday, Mr. Mamdani said he thought Israel, as well as countries with official religions like Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, should be held to the same standard of upholding equal rights.

But some rabbis, leaders and Jewish voters who have attended the events view Mr. Mamdani’s position as antisemitic because he focuses most intensely on Israel, denying Jews a right to self-determination.

Several weeks ago, Mr. Mamdani met with a group of liberal-leaning rabbis, according to someone familiar with the meeting, who insisted on anonymity to discuss a sensitive gathering that was intended to remain private. The person said the meeting ended with Mr. Mamdani and at least some attendees “totally apart from one another” on key issues.

Even a series of appearances last Thursday at the private sukkahs of several powerful Satmar Hasidic leaders in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, prompted some blowback.

At the stops, Mr. Mamdani sported a black velvet yarmulke popular with observant men and sat alongside community leaders wearing shtreimels, the round fur hat that some Hasidic men wear on holidays and Shabbat. Satmar Hasidim are traditionally among the ultra-Orthodox sects who support religious anti-Zionism and do not recognize the state of Israel.

“We are here to work with anyone who wants to work with us,” said Rabbi Moishe Indig, a leader of a Satmar Hasidic group, who has introduced Mr. Mamdani to other activists and rabbis in the community. “He wants to make sure that people know he’s a friend. He’s not an enemy and he wants to be everybody’s mayor.”

Kalman Yeger, an Orthodox assemblyman who once represented the Hasidic enclave of Borough Park as a city councilman, pushed back on social media: “Maybe he’ll exclude Williamsburg from his Globalized Intifada,” he posted.

Jeffrey Lerner, a spokesman for Mr. Mamdani’s campaign, said Mr. Mamdani has had “productive conversations” with faith leaders and “looks forward to continuing to build these relationships as the next mayor.”

The debate over when — and whether — anti-Zionism amounts to antisemitism has exposed deep fissures within the Jewish community, often along generational lines.

A broad majority of younger voters, along with a handful of more liberal rabbis, are backing Mr. Mamdani. He received a warm welcome when he attended Rosh Hashana services at Kolot Chayeinu, a progressive synagogue that includes a vocal self-described anti-Zionist contingent.

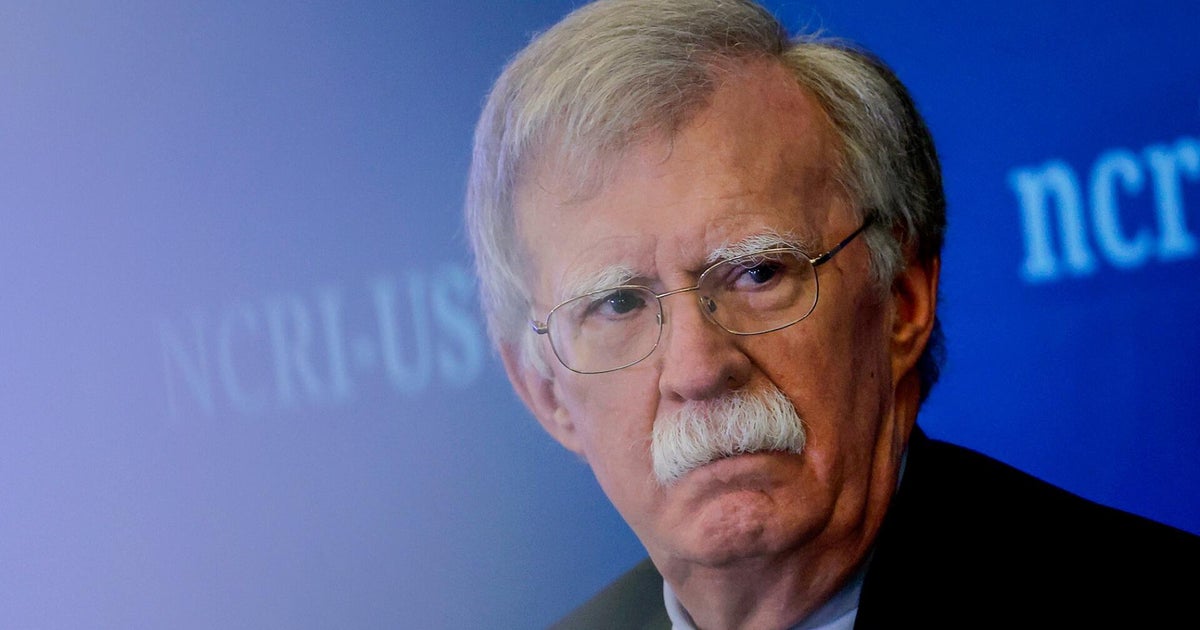

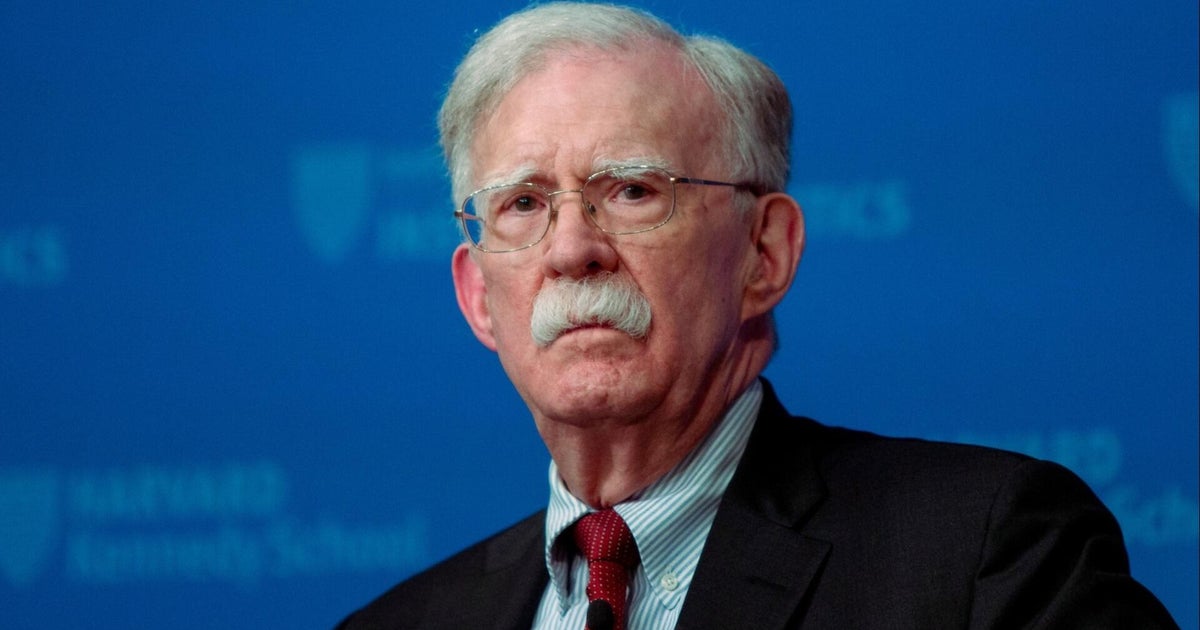

Image

Yet, even as polls suggest more New Yorkers are moving to Mr. Mamdani’s position on Israel, many Jewish voters remain opposed to his candidacy.

“The heart of the matter is, he is a committed ideologue, anti-Zionist,” said Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch, who leads Stephen Wise Free Synagogue, a Reform congregation on the Upper West Side. “Unless and until he addresses that fully and publicly, I think all of the efforts to try and soften his previous antagonism to Israel will fall short, and in fact will exacerbate the tension.”

Sixty percent of Jewish likely voters said they plan to back former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo in the race, while 29 percent support Mr. Mamdani, according to a Quinnipiac University poll released last week.

Mr. Cuomo, who is running as a moderate independent, has positioned himself as a vigorous defender of Israel who is best equipped to represent Jewish New Yorkers. In the days after Mayor Eric Adams suspended his re-election campaign, a number of Jewish groups endorsed him.

“The Mamdani policy initiatives will destroy New York City,” said Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz, the head of Kehilath Jeshurun, a prominent Manhattan orthodox congregation, in a video posted to his synagogue’s Facebook account last month.

But Mr. Cuomo has faced opposition from some more liberal Jewish voters. He’s also struggled to navigate mistrust within the Hasidic community over the coronavirus restrictions he imposed as governor on religious gatherings.

The divides have turned the mayoral race and Mr. Mamdani’s candidacy into fraught subjects for many congregations across the spectrum of Jewish religious practice in the city.

The mere rumor that Mr. Mamdani would attend services over the high holidays with Representative Jerrold Nadler at B’nai Jeshurun, the Upper West Side synagogue where the congressman is a member, prompted synagogue leaders to issue a public statement forcefully rejecting the idea of politics on a holy day.

And attendees at many meetings that have occurred have been given strict instructions not to discuss with reporters what Mr. Mamdani says, who attended the gathering or, in some cases, acknowledge that they even occurred at all.

Several rabbis acknowledged that having a strong relationship with the mayor would benefit their congregants and institutions. But they feared financial and public backlash from some of their congregants should such a gathering become public. They would not speak publicly about Mr. Mamdani’s candidacy or any efforts to organize a meeting.

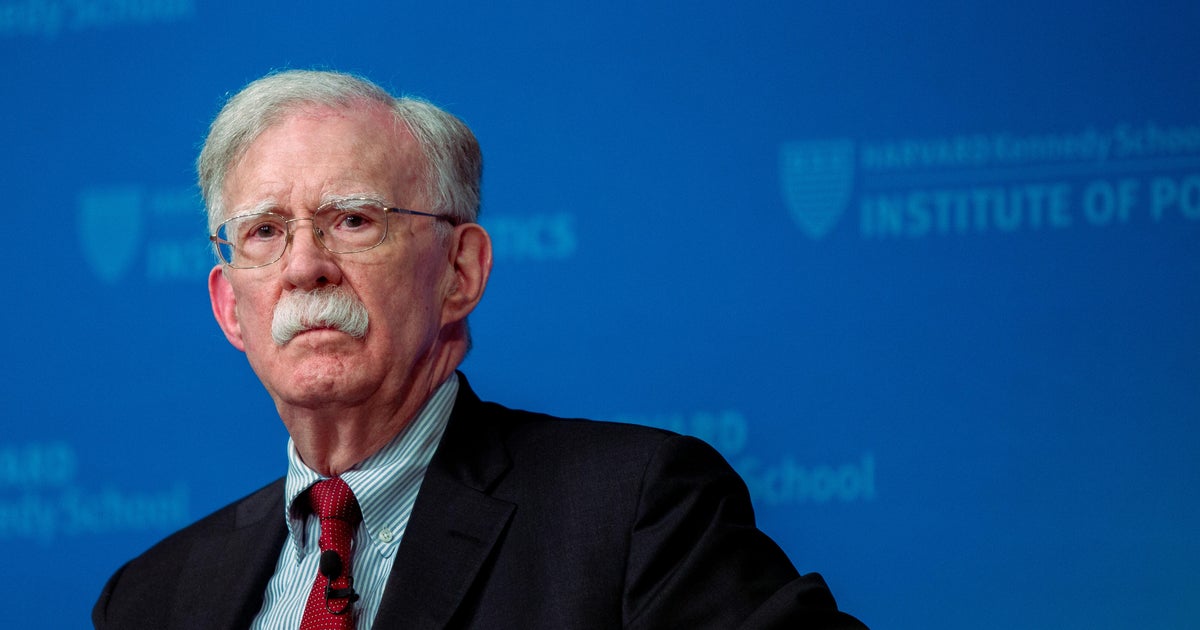

Image

One meeting that did occur, at Mr. Mamdani’s campaign office shortly before Yom Kippur, included Rabbi David Niederman, an influential Hasidic leader and president of the United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg and North Brooklyn, along with other leaders from the Satmar community, according to a person with direct knowledge of the meeting who insisted on anonymity to discuss it.

There, they discussed the community’s concerns around safety and antisemitism, the person said, recalling that at one point Mr. Mamdani appeared to tear up after hearing about how antisemitism had affected the community, and assured attendees that he understood the threats.

“Antisemitism is real, and I think that people are so anxious they don’t really know how to understand who Mamdani is exactly,” said Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum, the former head of Congregation Beth Simchat Torah, the largest L.G.B.T.Q. congregation in the country. “I am supporting him, but I understand the fear.”

Rabbi Kleinbaum, who met with Mr. Mamdani shortly after the primary in June, said she has been gratified by their discussions about the future of the city.

“I’ve had really great exchanges with him where I have been deeply honest and forthcoming,” she said. “I have felt engaged in a way that is inspiring.”

Rabbi Timoner stressed the importance of having an open dialogue with Mr. Mamdani, saying her congregants — including some who oppose him — were grateful he took the time to hear their concerns.

The receptions have also been mixed in other settings, even in private invitation-only gatherings like one hosted at the townhouse of Sandi DuBowski, a Jewish documentary filmmaker with ties to Orthodox and progressive Jewish communities. While he received a largely warm response, Mr. Mamdani’s views on Israel-related policies were greeted there with some skepticism, according to someone in attendance.

When Mr. Mamdani joined Lab/Shul, a liberal congregation, for the Kol Nidre service several weeks later, he was greeted with a standing ovation — but also a walkout by a handful of attendees and a flurry of angry messages to synagogue leaders after the holiday.

“Lab/Shul is not an ideological monolith, and this is just one more living expression of our community engaging in the messy middle,” said Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie in a statement. “We know that for some in our community, this choice was painful.”

Lisa Lerer is a national political reporter for The Times, based in New York. She has covered American politics for nearly two decades.

Katie Glueck is a Times national political reporter.

10 hours ago

2

10 hours ago

2

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·