Age has not withered One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Milos Forman’s barnstorming account of the men who were once labelled lunatics inside what was once called an asylum. Shifting social attitudes can’t blunt its barbed comedy or draw the sting of a drama that pits timid patients against the icy, rigid Nurse Ratched. Time, if anything, has only sharpened the film’s edges, so that it feels more lawless and hazardous than it did in the past. Lovingly dusted down and reissued for posterity, it swaggers into cinemas this week like Randle Patrick McMurphy into the Oregon state mental hospital.

Forman’s film is now 50, a solid, respectable age, except that Cuckoo’s Nest has never really been respectable, let alone staid and settled, and more resembles a disreputable uncle who struck gold and joined the country club. It was an orphan, an outlier, rejected by every major studio until United Artists picked it up; the unruly underdog that went on to clean up at the Oscars and become the second-highest-grossing picture of the year behind Jaws (1975).

Most movie classics are the industry’s equivalent of elder statesmen or museum exhibits, coddled by history or pinned under glass. Cuckoo’s Nest, though, continues to twist and turn in our grasp. It’s a film of its era – a dinosaur even – and yet it doesn’t feel dated and speaks across party lines. Cuckoo’s Nest loves freedom, self-sufficiency and the pursuit of personal happiness, and is therefore beloved by both old-school hippies and hard-right Maga types. Each side can claim that the film shares their values. Each sees itself in McMurphy while regarding the other side as Nurse Ratched.

The production was a scramble; it ran on adrenaline and confusion. Cuckoo’s Nest was produced by the 29-year-old Michael Douglas, who inherited the project from his father, Kirk, who longed to play McMurphy, the live-wire convict who galvanises the psych ward. And he was furious when the role went instead to Jack Nicholson, a younger, hotter property, fresh off the back of Chinatown (1974) and The Passenger (1975). Forman, a hero of the Czech New Wave, had been holed up in the Chelsea Hotel recovering from a nervous breakdown when he was hired to direct and brought his own experience of Eastern Bloc oppression to this purely American tale. “The communist party was my Nurse Ratched,” he explained.

The film was shot inside a working psychiatric facility, with medics and patients folded in amid the cast and crew. There was an arsonist employed in the art department. One inmate escaped through an open upstairs window (he injured himself in the fall and was promptly recaptured). The budget ballooned, tempers flared and the actors turned mutinous. Pretty much every day was a struggle, which served the material well, because the real-life drama spilled over and sparked. Arriving late on set, Nicholson was alarmed to note that many of his fellow performers seemed unable to break character. To reheat an old joke, you didn’t have to be mad to work on Cuckoo’s Nest, but it helped.

“Which one of you nuts has got any guts?” asks McMurphy, the hospital’s riotous new inmate, thereby setting himself and his flock on a collision course with the authorities in general and Ratched in particular. The comedy pops like a firework display. The dramatic scenes land with the force of a hammer.

Forman’s drama was based on the 1962 bestseller by Ken Kesey, the hippie founder of the Merry Pranksters, and was viewed at the time as a film of the left, a counter-cultural touchstone, although its language has since been appropriated and tweaked by the libertarian right. McMurphy hates bureaucracy, bridles at regulations and gives the patients a dose of undiluted machismo. The men are emasculated wrecks who need to rediscover their mojo. The women are either giggly sex workers or castrating mother-hens.

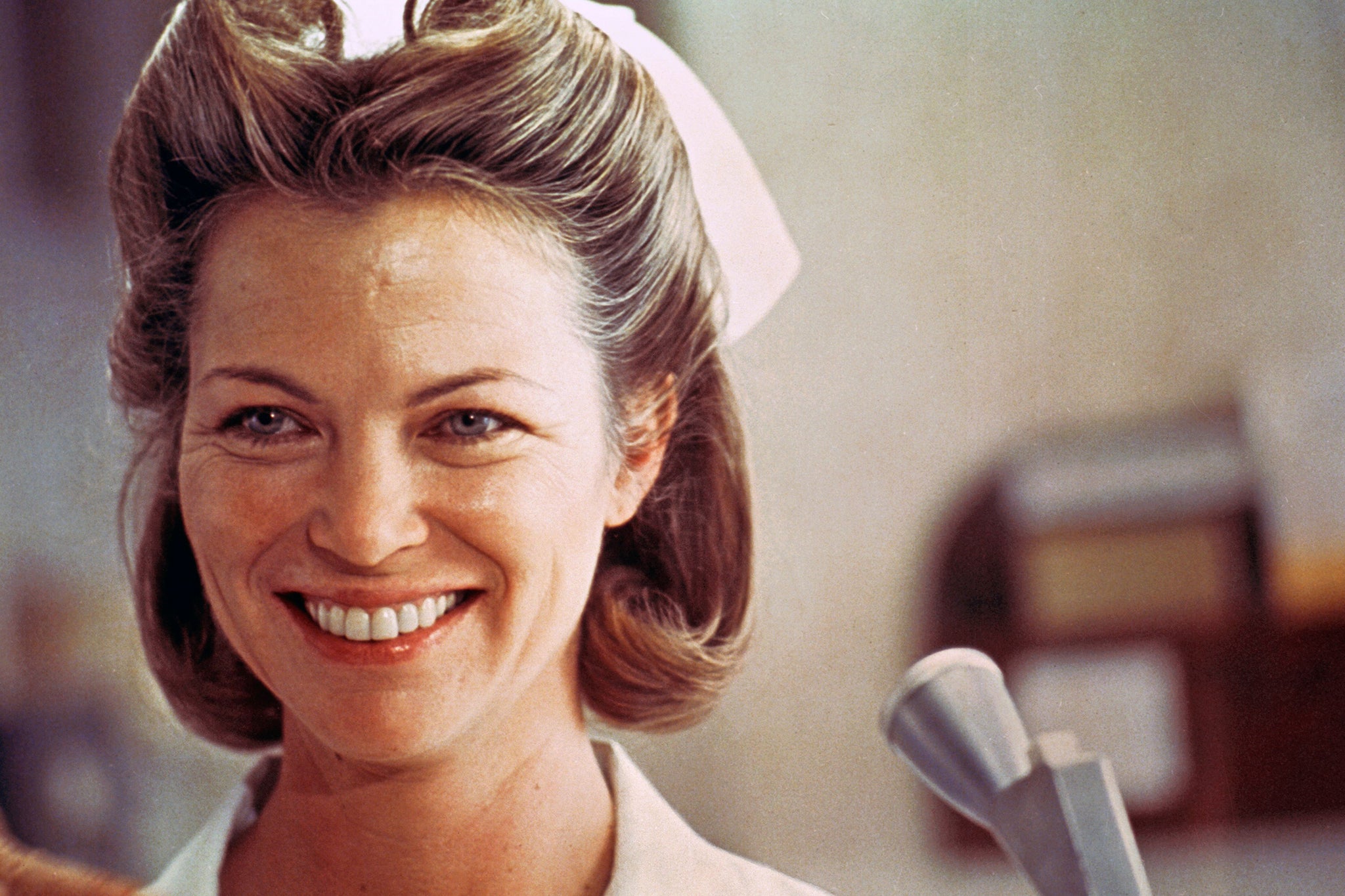

But the film is not without nuance and a sense of life’s tense complexities. Crucially, Louise Fletcher’s performance as Ratched ensures that Kesey’s monster stays human. She’s a harried professional, and as much a creature of her time as McMurphy. Ratched is outnumbered and the ward’s under siege. Small wonder, on balance, that she resorts to the jump leads.

Cuckoo’s Nest is one of those rare pictures that, if it catches you early, partially owns you forever. I stumbled across it on TV in my teens and briefly decided it must be the best film in the world. It was ecstatic and tragic and funny and fierce. It looked and smelled like real life, but it swelled and roared like great music. I later read that Forman’s grasp of English was so poor that he had to trust his ear during the improvised therapy sessions, following each actor’s voice as though it were an instrument in an orchestra and only calling cut when he heard a flat note. He had a habit, too, of keeping three cameras running throughout the scenes on the ward, to record every twitch, every scratch, every startled jerk of the head. Forman, one could say, directed in the manner of McMurphy: loose and easy, wild and free, so that the film gives the impression of pouring out of the screen, playing out in real time before our very eyes.

Rewatching it today, it’s clear it still resembles McMurphy, in good ways and bad, meaning that the film has its problems, numerous psychological hang-ups. Its critics have a point. Cuckoo’s Nest fumbles women, First Nation people and African-American men. Medically, too, the tale is boneheaded: sentimental but crass. It did for mental health nurses what Jaws did for sharks. It’s a film of the Seventies, it would never get made today, and yet its longing for freedom feels timeless, its battles are ongoing and its emotional arc stirs the blood.

And just as with every work of art that endures, its uglier aspects are all part of a piece. They add texture and context and connect it to the wider world. So I’ll always be happy to see this reappear for big birthdays, rolling in like a drunk, constantly geared towards mischief. It’s magnificently unreconstructed; it’s flawed, but it’s perfect. I wouldn’t change a single frame.

‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ is back in cinemas from 17 October

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·