The Paris Agreement has helped the world avoid dozens of dangerously hot days every year, according to new research marking the accord’s 10th anniversary.

But scientists warn that the planet is still heading for a “dangerously hot future” unless countries phase out fossil fuels faster.

The analysis, conducted by Climate Central and World Weather Attribution, notes that if governments meet their current emission-cutting targets and limit global warming to 2.6C this century, the world may experience 57 fewer extremely hot days per year than under a 4C scenario projected before the 2015 Paris Agreement was signed.

At 4C of warming, the planet would see an average of 114 extremely hot days a year. But if all countries deliver on their current targets, the number of such days could be roughly halved, the study says.

Researchers warned, however, that even 2.6C of warming would still expose billions of people to dangerous heat and widen global inequality.

“The Paris Agreement is helping many regions of the world avoid some of the worst possible outcomes of climate change,” Dr Kristina Dahl, vice president for science at Climate Central, said.

“But make no mistake – we are still heading for a dangerously hot future. The impacts of recent heatwaves show that many countries aren’t well prepared to deal with 1.3C of warming, let alone the 2.6C projected if – and it is a big if – they meet their current emissions pledges.”

The Paris Agreement set the goal of keeping global temperatures well below 2C and of continuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C, if possible.

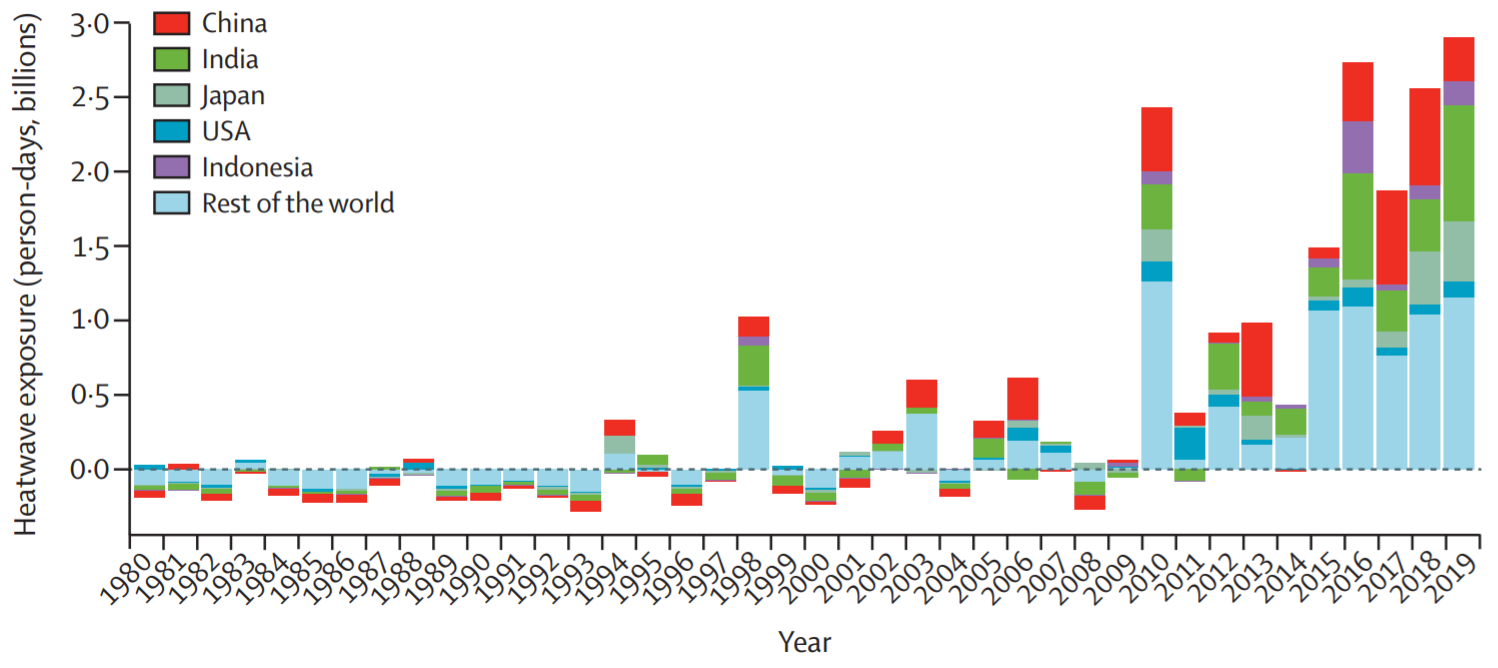

But global heating has already reached 1.3C above pre-industrial levels and the last 10 years have been the hottest on record, the World Meteorological Organisation said.

Analysis from the Met Office, University of East Anglia and the National Centre for Atmospheric Science found that 2024 was the hottest year on record and likely the first year exceeding 1.5C, sparking fears that the 1.5C limit could be breached soon if the pattern continued.

Researchers said that since 2015, an increase of just 0.3C had added 11 more hot days per year on average and made extreme heat events significantly more likely – 10 times in the Amazon, nine times in Mali and Burkina Faso, and twice in India and Pakistan.

“We are on track to exceed the 1.5C target of the Paris Agreement this century, but this doesn’t mean we need a new goal,” Dr Joyce Kimutai, researcher at the Centre for Environmental Policy, Imperial College London, said. “Warming has to be kept as far below 2C as possible.”

Professor Friederike Otto, climate scientist at Imperial College London and co-author of the study, said the Paris Agreement was “a powerful, legally binding framework that can help us avoid the most severe impacts of climate change”.

“However, countries need to do more to shift away from oil, gas and coal,” she said. “We have all the knowledge and technology needed to transition away from fossil fuels, but stronger, fairer policies are needed to move faster.”

The study revisited six major heat events in southern Europe, West Africa, Australia, Asia, North and Central America, and the Amazon. It found that at 4C of warming, such events would be five to 75 times more likely than today and up to 6C hotter. Limiting warming to 2.6C would reduce the likelihood to three to 35 times, with temperature increases of 1.5 to 3C.

“Every fraction of a degree matters. From 2015 to 2023, with an additional 0.3C of warming, the world now sees an average of 11 more hot days per year,” said Joseph Giguere, research associate at Climate Central.

“That’s not just a number – delaying the shift away from fossil fuels means millions more people are exposed to life-threatening conditions.”

The change in climate is costing billions of dollars in disasters, hitting poorer countries harder.

A recent report by the International Institute for Environment and Development found that eight vulnerable countries in Asia and Africa faced losses of about £17bn every 20 years – roughly equivalent to Senegal’s annual GDP.

“The majority of the world, primarily in low resource settings, is barely coping with extreme heat,” Emmanuel Raju, director of Copenhagen Centre for Disaster Research, said. “This is a problem of injustice as people are pushed beyond their limits to cope and adapt.”

One of the major achievements since the adoption of the Paris Agreement has been improvements in adaptation efforts. Almost half of all countries now have early warning systems and at least 47 have heat-action plans in place, the report says.

Still, experts cautioned, the progress remained uneven.

“The Paris Agreement is best known for its warming targets but we have also made important progress on adaptation since its signing,” Roop Singh, head of urban and attribution at the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre, noted. “The danger of heat will only increase this century, so it is crucial that every country implements measures that help keep people safe.”

The study comes just days before the Cop30 summit in Belem, Brazil, where countries will once again gather to discuss progress in tackling the climate crisis against the backdrop of increasing scepticism and pushback against climate science in the US.

Researchers urged governments to accelerate emission cuts, expand adaptation finance, and strengthen public-health systems to deal with escalating heat risks.

“The Paris Agreement works,” Bernadette Woods Placky, chief meteorologist at Climate Central, said.

“It shows that when countries come together, they can accelerate emission cuts for a safer future. The landmark accord is making a difference.”

.jpeg)

.jpeg?width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800)

.png?trim=0,0,0,0&width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800)

.jpg?trim=0,0,0,0&width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800)

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·