Costumes can define a film the instant they step on screen. They set time and place, hint at character, and sometimes spark debates that spill far beyond the theater. When designs clash with cultural expectations, historical records, or public sensibilities, they become flashpoints that people talk about for years.

This list looks at outfits that ignited conversation for very different reasons, from cultural representation to sexuality to political symbolism. You will find the designers who built them, the decisions that drove the look, and the specific reactions that followed. You will also see where studios responded, since distribution choices often shaped how wide those debates traveled.

Princess Leia’s metal bikini in ‘Star Wars: Return of the Jedi’ (1983)

Disney

DisneyThe bikini worn by Carrie Fisher was developed by costume designer Aggie Guerard Rodgers with sculptural input from Nilo Rodis-Jamero, using rigid plates over a fabric foundation to keep it stable on set. The design was engineered to take stunt work and desert heat into account, with multiple duplicates created for the Tatooine scenes released through 20th Century Fox.

Public reaction focused on how revealing the costume was and how widely it was merchandised, which led to recurring debates about objectification and toy imagery tied to a family franchise. The look entered pop culture immediately, and later archive displays documented the build techniques and fittings that made it practical for action while still matching the production’s fantasy aesthetic.

Kirk Lazarus’s blackface transformation in ‘Tropic Thunder’ (2008)

Paramount Pictures

Paramount PicturesCostume designer Marlene Stewart built a Vietnam-era wardrobe for Robert Downey Jr.’s character that incorporated period gear and a prosthetic-supported complexion change as part of the film’s satire. The look was calibrated with makeup and wardrobe tests so the final image stayed consistent across locations under Paramount’s release.

The character’s appearance triggered controversy around blackface and representation, which led to public statements from the filmmakers explaining the satirical intent and the plot’s criticism of the practice. Press materials and awards screenings repeated those clarifications, but the costume remains a frequent case study in how satire can collide with lived experience.

Geisha wardrobes in ‘Memoirs of a Geisha’ (2005)

Sony Pictures

Sony PicturesColleen Atwood led extensive research into kimono types, obi tying, and seasonal patterns, then adapted silhouettes for movement and camera framing. The production commissioned custom textiles and coordinated kimono layers by story beat, with Sony Pictures Releasing bringing the film to a broad international audience.

Discussion centered on cultural authenticity and the casting of Chinese actors as Japanese geisha, which placed extra scrutiny on the wardrobes. Critics and cultural commentators pointed out where screen-friendly adjustments diverged from tradition, while museum exhibits later showcased the craftsmanship behind the garments alongside context about what was changed for film.

Tonto’s crow-headdress in ‘The Lone Ranger’ (2013)

Disney

DisneyCostume designer Penny Rose drew from an imagery source that included a 1990s Kent Monkman painting featuring a bird-on-head motif, then translated the idea into a practical rig that could survive horseback work. The rest of Tonto’s clothing blended buckskin pieces, beadwork, and aged textures, and the film was distributed by Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

The headdress prompted criticism from Native American voices about cultural specificity and stereotype. Public outreach included consultations that were cited by the filmmakers, yet the costume remained a focal point in coverage about representation in Westerns and how singular images can set a tone for an entire production.

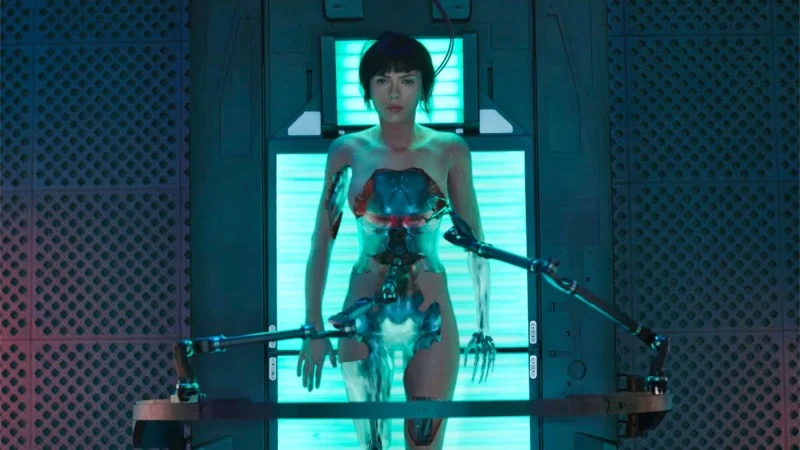

Major’s synthetic body suit in ‘Ghost in the Shell’ (2017)

Paramount Pictures

Paramount PicturesDesign duo Kurt and Bart created a full-coverage suit that imitated skin while remaining modest under lighting, using molded panels and printed textures to echo cybernetic anatomy. Multiple suits were built for water, wirework, and close-up shots, and the film reached theaters through Paramount Pictures.

The look became entangled with broader complaints about whitewashing and adaptation choices from the original anime. The body suit’s near-nude effect fueled debates about how the story used the character’s physical form, and production notes later detailed why the team rejected actual nudity in favor of engineered materials.

The droogs’ codpieces and whites in ‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971)

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.Milena Canonero assembled the droogs’ signature look from athletic supporters, bowler hats, and white shirts stiffened for a stark graphic effect. Stanley Kubrick encouraged found elements, which led to the iconic eyelash accent and cane, and Warner Bros. handled the film’s release.

The costume became a symbol for the film’s violence and sexual menace, drawing censure boards’ attention in several countries. Archival materials show how simple garments were modified to feel uniform and uncanny, which amplified censors’ concerns and helped cement the outfit as a lightning rod in discussions about screen morality.

Dance team outfits in ‘Cuties’ (2020)

Netflix

NetflixThe production fitted the preteen characters with competition-style dancewear modeled on real European teams, combining sequins, crop tops, and performance sneakers. Wardrobe continuity tracked how the outfits escalated in flashiness across routines, and the film reached a global audience via Netflix.

Criticism focused on sexualization in marketing images and how the choreography and costumes were framed on screen. Public statements clarified the film’s intent to critique that culture, yet the wardrobe’s design and presentation remained central to petitions, media coverage, and content advisories in several regions.

Confederate uniforms and hoop gowns in ‘Gone with the Wind’ (1939)

MGM

MGMWalter Plunkett produced a vast wardrobe that included hand-dyed hoop gowns, uniforms with period-accurate insignia, and the well-known curtain dress constructed to read clearly in Technicolor. The release through Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer expanded the film’s reach and helped make the costumes widely imitated.

The clothing later drew renewed criticism for romanticizing the antebellum South and the Confederacy. Restoration screenings and streaming presentations have added historical disclaimers, and retrospectives now contextualize the garments within a narrative that has been reassessed for its portrayal of race and history.

Klan robes in ‘The Birth of a Nation’ (1915)

Epoch

EpochThe production standardized white robes and hoods to create a stark, uniform look on screen, tailoring the garments for horseback and group movement. Distribution through the Epoch Producing Company helped the film tour extensively, which spread the imagery across the United States.

The costume design became inseparable from the film’s racist narrative and from the real-world adoption of similar regalia by the Ku Klux Klan in the years that followed. Modern film history programs cite these robes as a cautionary example of how cinematic costuming can influence extremist iconography outside the theater.

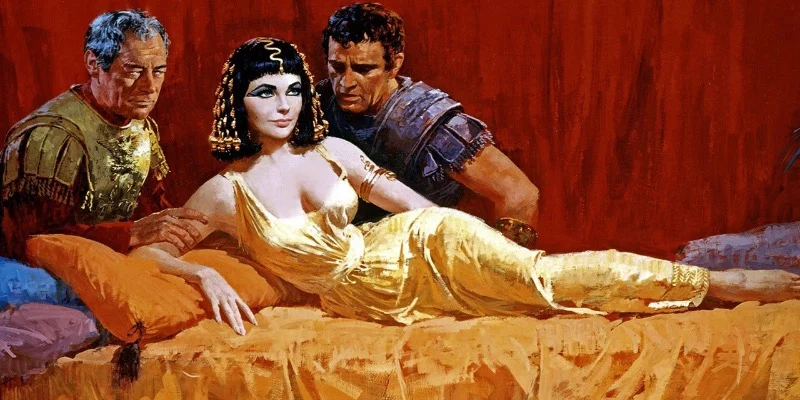

Elizabeth Taylor’s gilded looks in ‘Cleopatra’ (1963)

20th Century

20th CenturyIrene Sharaff, Vittorio Nino Novarese, and Renié built hundreds of pieces for Elizabeth Taylor, from gold-leafed headdresses to structured column gowns. The team used metal mesh, elaborate beadwork, and custom wigs to create silhouettes that popped in widescreen, and 20th Century Fox distributed the film.

While the costumes won Oscars, they also drew criticism for Orientalist fantasy and for sacrificing historical accuracy to spectacle. Production histories document the extraordinary cost of the wardrobe along with the publicity machine that centered Taylor’s outfits, which shaped public expectations about what “Egyptian” meant on screen for decades.

Brüno’s runway-shock wardrobe in ‘Brüno’ (2009)

Universal Pictures

Universal PicturesThe costume department created flamboyant outfits designed to provoke reactions in unscripted situations, from harnesses to high-gloss metallic pieces that allowed fast changes during real encounters. Quick-release construction and concealed mics were built into garments, and the film was released by Universal Pictures.

Controversy followed because many scenes pushed into cultural and political hot zones, which turned the clothing into a tool for confrontation. Legal reviews and region-specific edits accompanied the rollout, and the wardrobe’s design was repeatedly cited in complaints to broadcasters and festival organizers.

Neon ski masks and bikinis in ‘Spring Breakers’ (2012)

A24

A24Costume designer Heidi Bivens sourced real streetwear and budget swimwear, then combined them with candy-colored balaclavas to create a youth-culture collage. The approach emphasized authenticity by shopping local stores near shooting locations, and A24 brought the film to theaters.

Debate centered on depicting underage characters in sexualized outfits even though the actors were adults. The visual contrast of playful colors with crime imagery became a talking point in reviews and interviews, which kept the wardrobe at the center of the film’s reception long after its release.

Showgirl sets and G-strings in ‘Showgirls’ (1995)

United Artists

United ArtistsEllen Mirojnick built stage costumes with tear-away features, crystal embellishment, and rigid corsetry to withstand choreography and quick changes. The scale of the wardrobe required a dedicated maintenance crew to repair beading between takes, and United Artists handled domestic distribution.

The explicitness of the outfits contributed to an NC-17 rating and to theater chains declining bookings. Industry coverage tied the box office performance to how the costumes were marketed, and home video success later shifted the conversation toward craftsmanship and stage durability.

Xerxes and the Persians in ‘300’ (2006)

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.Michael Wilkinson designed stylized armor and jewelry that leaned into graphic-novel exaggeration, using molded leather, chain, and body paint to emphasize physique. The Spartans’ minimal kit contrasted with ornate Persian looks, and Warner Bros. released the film worldwide.

Iranian commentators and historians criticized the portrayal of Persians, with costumes cited as reinforcing negative caricatures. Behind-the-scenes materials outline the aesthetic logic drawn from the source comic, while academic responses documented how those choices influenced audience perceptions of ancient cultures.

Hanfu-inspired outfits in ‘Mulan’ (2020)

Disney

DisneyCostume designer Bina Daigeler researched multiple dynastic styles, then blended elements into screen-friendly armor and civilian dress for clarity and movement. The team developed patterned jacquards and leather-look lamination for durability during stunt work, and Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures managed the global rollout.

Historians and viewers pointed out anachronisms in hair, accessories, and garment cuts that did not align with the story’s implied period. Interviews and featurettes explained the choice to mix references for readability, but the discussion highlighted how historical Chinese dress on screen is scrutinized for accuracy and regional specificity.

Share the ones you think we missed or got right in the comments so we can keep the conversation going.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·