Egyptian mythology overflows with remarkable beings—some protective, some terrifying, and many that blurred the line between animal, symbol, and deity. These creatures populated funerary texts, temple walls, and everyday amulets, shaping beliefs about creation, kingship, and the afterlife from the Early Dynastic period through the Greco-Roman era.

Below are fifteen of the most noteworthy creatures you’ll meet in Egyptian lore. Each one ties to specific rituals, temples, or texts—like the Book of the Dead, Pyramid and Coffin Texts, or later magical papyri—and many also lived on as royal emblems, tomb guardians, or talismans people wore for protection.

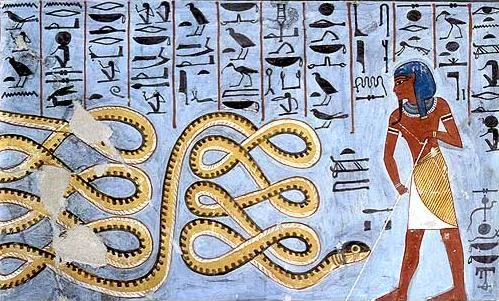

Apep (Apophis)

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsApep is the colossal serpent who embodies chaos and eternal night, opposing the sun god Ra. In underworld books such as the Amduat, he attempts to halt the solar barque each night, forcing gods and protective spirits to bind, cut, or burn him so dawn can return. Ritual texts include spells and effigies designed to “overthrow Apep,” showing how seriously Egyptians treated the threat of cosmic disorder.

Priestly rites against Apep were practical religious acts, not myths for entertainment. They called for crushing serpent figures, spitting on images, or piercing wax models to neutralize chaos. This nightly battle explained eclipses, storms, and other disruptions as moments when Apep briefly gained ground before being subdued again.

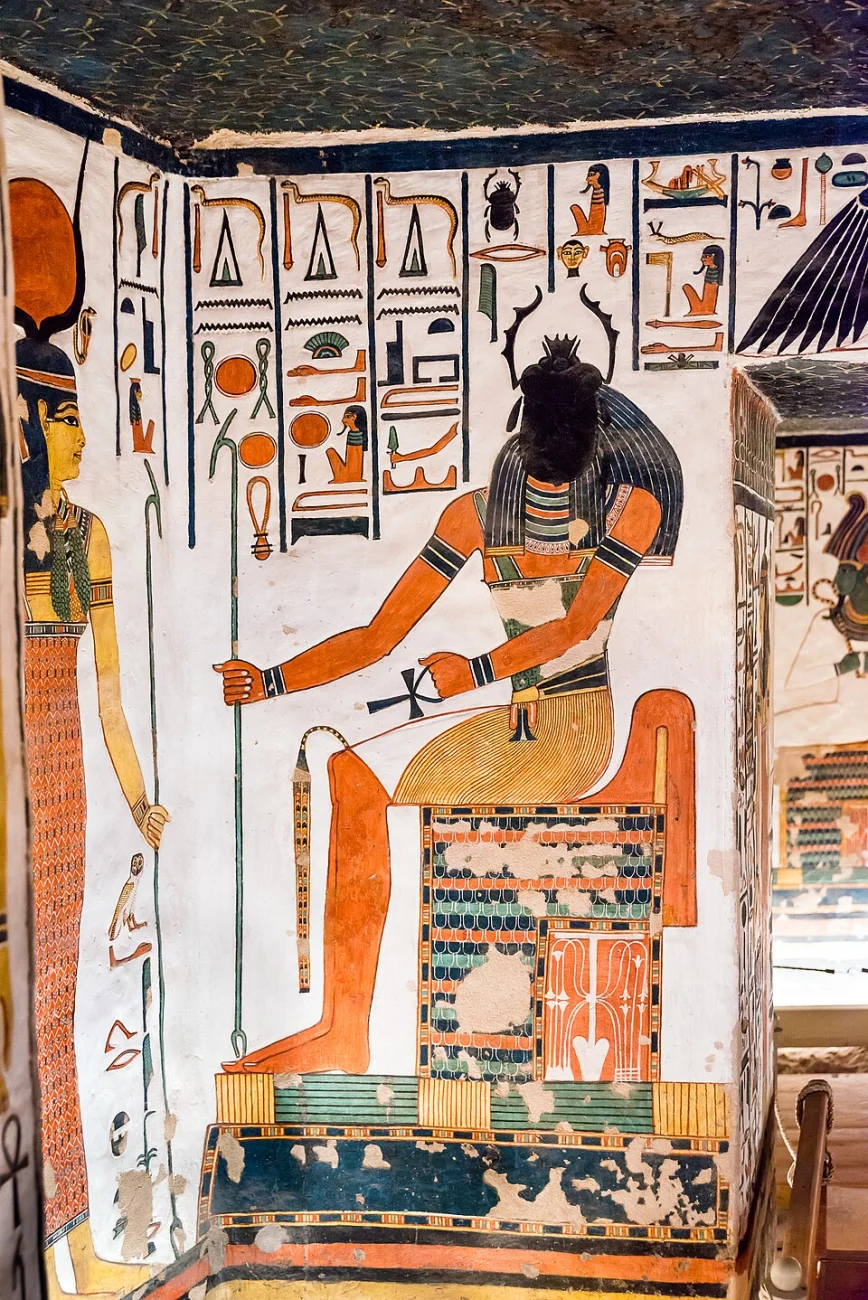

Ammit

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsAmmit—often depicted with a crocodile’s head, a lion’s forequarters, and a hippopotamus’s hindquarters—waits beside the scales in the Hall of Ma’at. When a deceased person’s heart fails to balance against the feather of Ma’at, Ammit devours it, ending the person’s hope of an afterlife. This composite form draws on Egypt’s most dangerous animals to signal total spiritual annihilation.

Texts and tomb scenes present Ammit as a functionary of divine justice rather than an indiscriminate predator. Her role underscores how moral order governed the afterlife: the righteous passed on, while the unworthy ceased to exist. Ammit’s presence thus reinforced ethical conduct and the centrality of Ma’at in life and death.

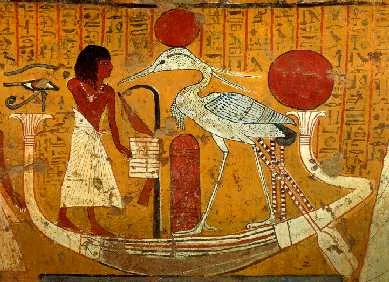

Bennu

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsThe Bennu is a radiant wading bird—often heron-like—linked with creation and rebirth. It perches on the primordial mound at Heliopolis, heralding the first sunrise and the cyclical renewal of life. The Bennu’s periodic self-renewal inspired later Greek ideas of the phoenix, but in Egypt it specifically expressed solar and cosmogonic themes anchored to the cult of Ra-Atum.

Temple reliefs and funerary papyri show the Bennu atop sacred symbols such as the benben stone. Amulets and heart scarabs sometimes bear Bennu iconography, promising regeneration to the deceased. Its association with time, new cycles, and the eternal return made the bird a potent emblem in royal and funerary contexts.

The Sphinx

PharaohCrab (Wikimedia Commons)

PharaohCrab (Wikimedia Commons)The Egyptian sphinx is a lion’s body with a human head, symbolizing royal power, vigilance, and the sun’s strength. The most famous example—the Great Sphinx of Giza—was carved from bedrock in the Old Kingdom and aligned with solar cults and the pyramid complex. Unlike later Greek sphinxes, Egyptian sphinxes are protectors of sanctuaries and kingship.

Sphinx avenues flanked processional ways at sites like Thebes, while statues and reliefs show pharaohs as sphinxes trampling enemies, asserting cosmic order. Small sphinx figures also served as votives, connecting worshippers to royal ideology and divine guardianship at temple entrances and sacred precincts.

Serpopard

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsSerpopards—leopard bodies with elongated, serpent-like necks—appear in Predynastic and Early Dynastic art, including ceremonial palettes. They likely represent a concept of untamed, foreign power subdued by kingship, since rulers are shown controlling or yoking them during foundational state rituals.

Although not tied to a specific cult, serpopards help chart how Egyptians used hybrid creatures to visualize control over disorder and distant lands. Their appearance in early iconography illustrates how the emerging state projected authority through composite beasts that symbolized what lay beyond domesticated, ordered Egypt.

Uraeus

GoShow (Wikimedia Commons)

GoShow (Wikimedia Commons)The Uraeus is the rearing cobra worn on royal crowns, denoting sovereignty, divine protection, and the power to strike enemies with fiery breath. It personifies the goddess Wadjet of Lower Egypt and, when paired with the vulture of Nekhbet, expresses the unification of the Two Lands. The emblem appears on diadems, temple lintels, and protective amulets.

In texts, the Uraeus can burn adversaries and guard sacred spaces, acting as a living flame for the king and gods. Its consistent placement on crowns, gateways, and solar disks ties it to both earthly kingship and solar theology, reinforcing the ruler’s sanctioned role in maintaining Ma’at.

Taweret

Jeff Dahl (Wikimedia Commons)

Jeff Dahl (Wikimedia Commons)Taweret is a hippopotamus-bodied, crocodile-tailed, leonine-limbed protector of childbirth and the household. Her image appears on amulets, beds, and feeding bowls, where she safeguards mothers and infants from malevolent forces. Taweret’s composite anatomy draws from animals known for strength and ferocity, redirected here to domestic protection.

Household cult items frequently depict Taweret alongside Bes, another protective being, indicating a practical, everyday religious focus beyond major temples. Her popularity persisted for millennia, with images found from the Middle Kingdom through the Late Period and into the Greco-Roman era, attesting to her enduring role in family life.

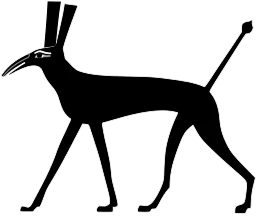

The Set Animal (Sha)

PharaohCrab (Wikimedia Commons)

PharaohCrab (Wikimedia Commons)The Set animal—called the sha—is an enigmatic composite creature with a curved snout, tall rectangular ears, and a forked tail, serving as the emblem of the god Set. Its form does not match any real species, though scholars compare it to stylized canids or an amalgam of desert animals, marking it as distinctly other.

The sha appears on standards, scepters, and temple reliefs from early periods onward, signaling power over arid frontiers and turbulent forces. Its persistent use highlights how Egyptians encoded complex theological ideas—like ambiguity and liminality—through a unique creature form reserved for a challenging but essential deity.

The Scarab (Khepri)

Gabana Studios Cairo (Wikimedia Commons)

Gabana Studios Cairo (Wikimedia Commons)The scarab beetle symbolizes Khepri, the morning sun that renews itself each day. Egyptians saw the dung beetle’s habit of rolling a ball as a natural analogue for the sun’s daily journey, mapping observable behavior onto cosmology. Scarab amulets became the most widespread personal objects in Egypt, used for protection, identity, and funerary rites.

Heart scarabs inscribed with spells were placed on mummies to secure the deceased’s transformation and truthful speech at judgment. Beyond burials, scarabs served as seals and jewelry, carrying images and names that tied everyday life to solar rebirth and cosmic order through a humble but potent creature.

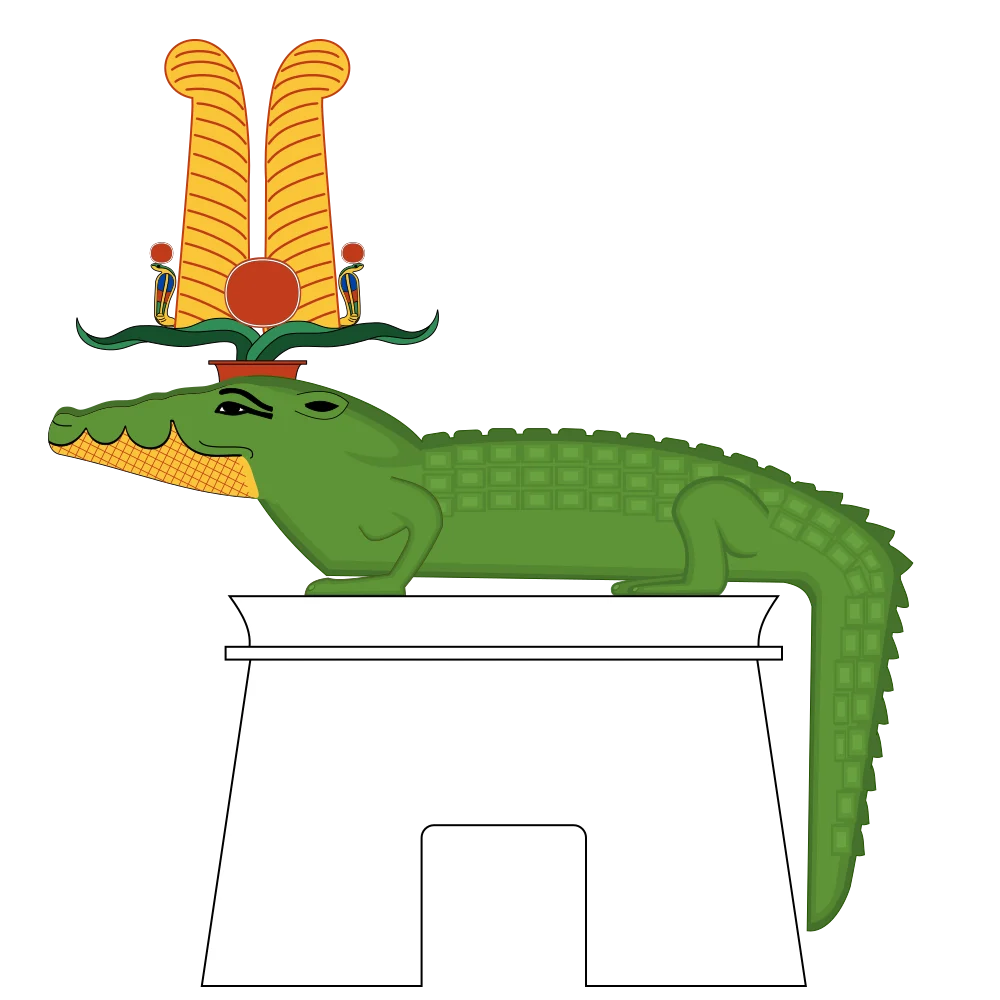

Sobek’s Sacred Crocodile

PharaohCrab (Wikimedia Commons)

PharaohCrab (Wikimedia Commons)Crocodiles, sacred to Sobek, were venerated especially in the Fayum and at Kom Ombo. Temples maintained live crocodiles, sometimes adorned with jewelry, and mummified them after death. The animal’s strength and aquatic domain linked Sobek to fertility, military prowess, and the Nile’s life-giving floods.

Archaeological finds include crocodile mummies, hatchling burials, and votive figures dedicated by worshippers seeking favor or protection. In official ideology, the crocodile’s fearsome reputation translated into patronage for kings and soldiers, while local cults associated it with water management, agriculture, and communal well-being.

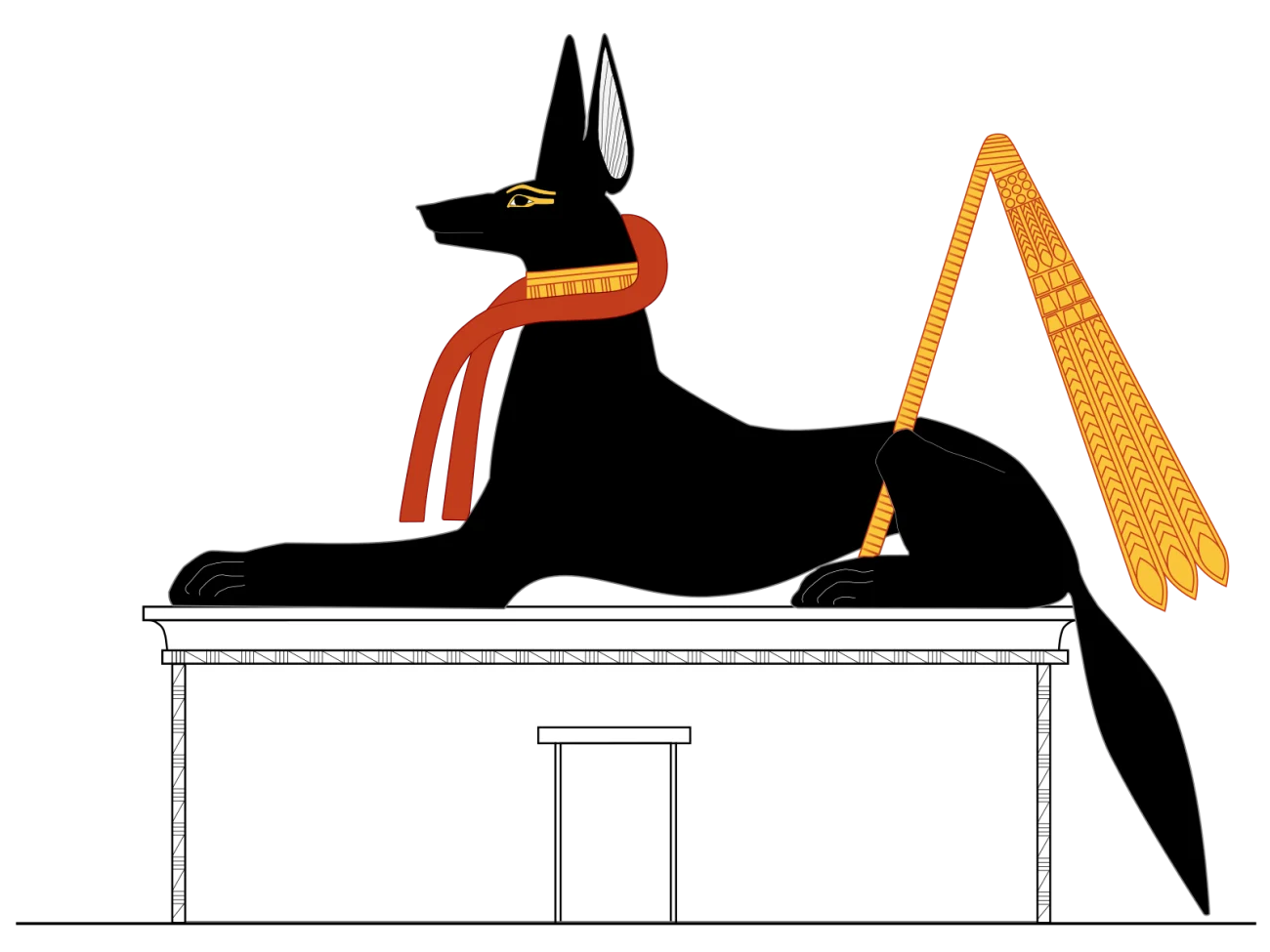

Anubis’s Jackal

PharaohCrab (Wikimedia Commons)

PharaohCrab (Wikimedia Commons)The jackal—emblem of Anubis—became the guardian of cemeteries and the patron of embalmers. Desert canids prowled necropolises, so Egyptians cast the jackal as a vigilant sentinel who watched over the dead and the processes that prepared them for eternity. Anubis standards marked processions and ritual spaces tied to mummification.

Funerary papyri show jackal forms overseeing the weighing of the heart, guiding purification rites, and protecting tomb entrances. Amulets, coffin paintings, and canopic equipment used jackal imagery to secure preservation, proper rites, and safe passage through the underworld’s gates and judges.

Mehen

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsMehen is the great serpent who coils around Ra’s solar barque, shielding the sun god from danger during the nightly voyage. Unlike Apep, Mehen is protective, sometimes shown encircling gods or the blessed dead. Board games named after Mehen—found in Old Kingdom contexts—hint at an early, widespread recognition of this guardian serpent.

In underworld texts, Mehen’s coils form living fortifications that absorb or deflect attacks. The image of a benevolent serpent guarding divine order counters the purely destructive serpent motif, illustrating how Egyptian thought assigned different moral valences to similar creature forms based on role and context.

The Ba-Bird

Jeff Dahl (Wikimedia Commons)

Jeff Dahl (Wikimedia Commons)The ba of a person—their mobility and personality—was often depicted as a human-headed bird that could leave the tomb by day and return by night. Tomb scenes show the ba-bird visiting the mummy, receiving offerings, and traveling between the living world and the necropolis. This image explained how the deceased interacted with family cults and festivals.

Texts prescribe offerings and rites to nourish the ba so it can move freely and unite with the akh, the “effective” transfigured state. Figures of the ba-bird on coffins and stelae provided a visual guarantee of that movement, ensuring the deceased’s continued agency within the ordered cosmos.

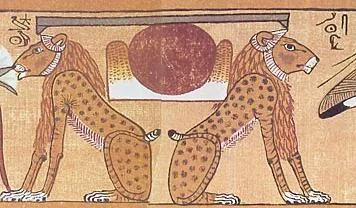

Aker (The Double Lion)

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsAker appears as two back-to-back lions guarding the horizon—yesterday and tomorrow—through which the sun travels. This earth-deity creature marks the liminal thresholds the sun crosses at sunrise and sunset, standing as a sentinel over passages between worlds and times. The double lion motif frames gateways and solar scenes in funerary art.

In spells, Aker stabilizes the underworld’s gates, restrains serpents, and secures the solar path. By embodying paired lions facing opposite directions, Aker integrates timekeeping, geography, and protection, reinforcing the reliable rhythm of day and night that sustained both earthly life and the afterlife journey.

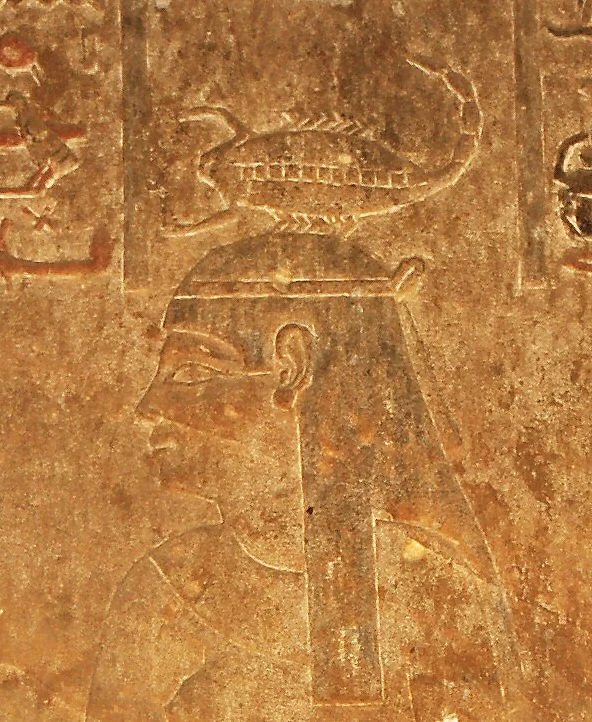

The Scorpion of Serqet

MatthiasKabel (Wikimedia Commons)

MatthiasKabel (Wikimedia Commons)Scorpions—sacred to the goddess Serqet—symbolized protection against venom and the safe “breath” needed for life. Amulets, wands, and bedside objects invoked Serqet to ward off bites and stings, a real concern in Egypt’s environment. In funerary contexts, she helps guard canopic equipment and supports the revival of the deceased.

Medical-magical texts include incantations and remedies that invoke scorpion imagery to neutralize poison. Temple reliefs and coffin inscriptions place Serqet and her creature alongside other guardians, creating a comprehensive protective network around the body, the vital organs, and the thresholds of the tomb.

Have a favorite creature or a detail we missed—drop your thoughts in the comments and join the discussion!

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·