Ancient Egypt shaped a complex pantheon of deities who governed everything from the annual Nile flood to the journey of the sun across the sky. Power in this world meant the ability to create, to protect, to heal, and to rule both the living and the dead. It also meant control over maat which is the principle of cosmic order and truth that kept creation balanced.

Priests maintained these bonds through rituals and offerings while myths explained how each god used authority in specific domains. Temples acted as earthly homes where images of the gods received daily care. The stories below focus on what each deity governed, where they were worshiped, and how their roles connected to kingship, magic, warfare, or the afterlife.

Nephthys

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlNephthys was associated with protection of the dead and the liminal spaces between worlds. She appeared in funerary scenes with Isis and often supported the deceased during mummification and burial. Her emblem included the hieroglyphs for house and basket placed upon her head which spelled her name.

Cult activity for Nephthys is attested in several cities including Heliopolis and Memphis. In temple liturgy she functioned as a guardian of sarcophagi and as a mourner who aided resurrection rites. Her protective spells were invoked on coffins and amulets to keep harmful forces away during the journey to the west.

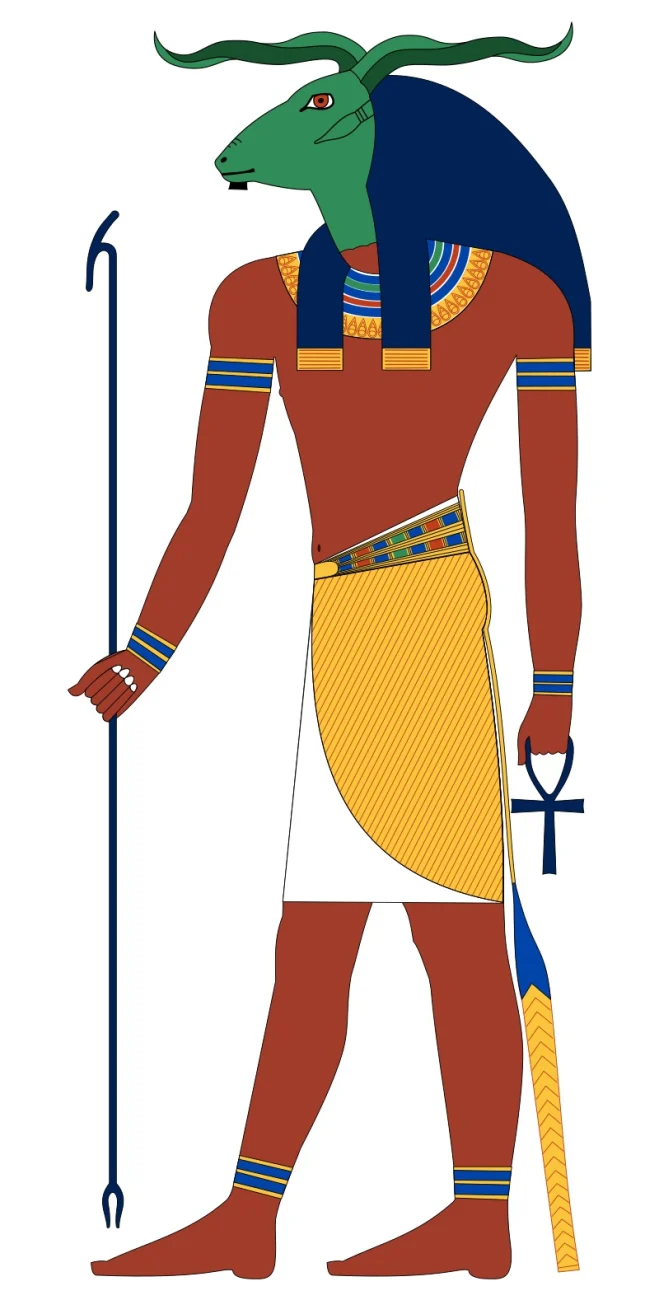

Khnum

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlKhnum was a creator god linked to the source of the Nile and to the potter’s wheel. In art he shaped human bodies and even the ka on his wheel then placed them within the womb. His ram headed form connected him to virility and regeneration.

His main cult center was Elephantine at Aswan where the Nile flood could be observed at first rise. Festivals celebrated the life giving waters that he controlled. In temple inscriptions Khnum was praised for fashioning the bodies of gods and kings which gave him an essential role in the creation of order.

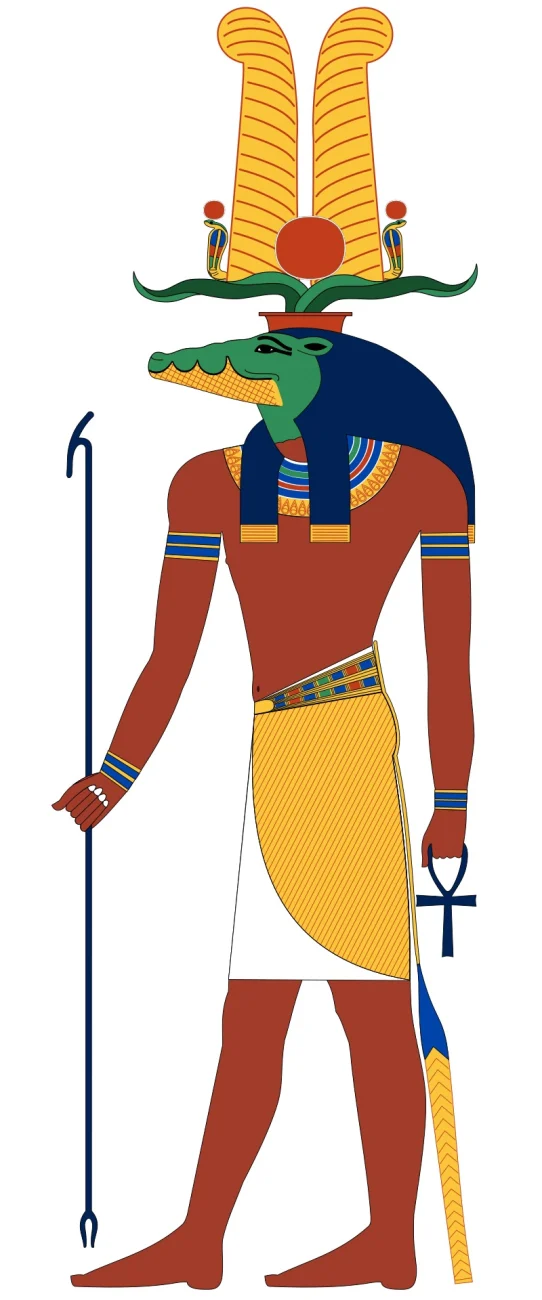

Sobek

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlSobek embodied the strength and unpredictability of crocodiles and therefore guarded waters and marshes. He was invoked for protection in areas where crocodiles were common and for military vigor during campaigns. His iconography showed a crocodile or a man with a crocodile head wearing a headdress of feathers and sun disk.

Important cult centers included the Faiyum region and Kom Ombo. At Kom Ombo a double temple honored both Sobek and Horus the Elder which emphasized balance between ferocity and kingship. Priests kept sacred crocodiles that were adorned with jewels and mummified after death to ensure the continued favor of the god.

Hathor

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlHathor governed joy, music, fertility, and maternal care while also guiding souls to the afterlife. She appeared as a cow or a woman with cow ears and was called Mistress of the West for welcoming the dead. She offered nourishment through the sycamore tree and was associated with turquoise mines in Sinai.

Her most prominent temple stands at Dendera where zodiac ceilings and ritual chambers survive in good condition. Festivals featured music and dance that honored her as lady of love and celebration. The goddess also protected miners and travelers and was invoked by women during childbirth for safety and health.

Sekhmet

Sekhmet personified the burning power of the sun and the force of plagues and war. She was depicted as a lioness headed woman whose breath created the desert wind. Texts describe her as the Eye of Ra who punished enemies of the divine order when unleashed.

Her cult was strong in Memphis where she was linked to Ptah and Nefertum as part of a triad. Physicians and magicians appealed to Sekhmet for protection against epidemics and for the reversal of illness. Thousands of granite statues dedicated to her attest to large scale state sponsored devotion that sought to harness and pacify her power.

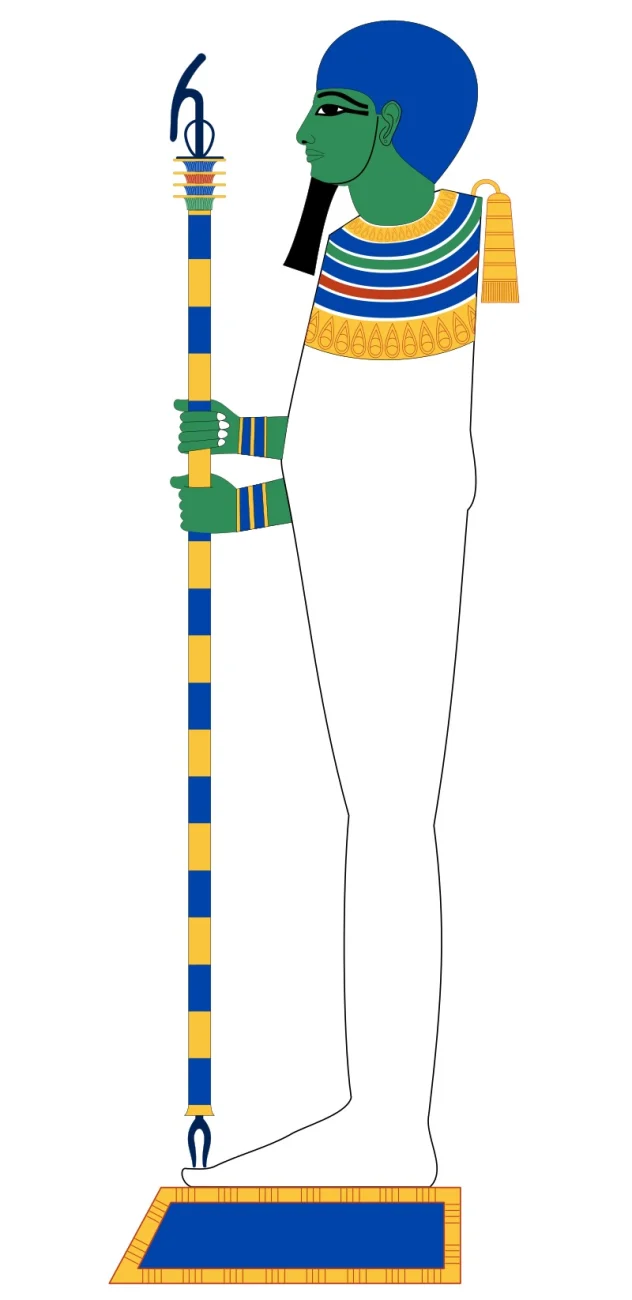

Ptah

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlPtah was a creator and craftsman god who brought the world into being through thought and speech. As patron of artisans he oversaw architecture metalwork and sculpture. His image showed a mummiform man holding a staff that combined symbols of life stability and power.

Memphis served as his chief cult center and royal building programs credited him with inspiring designs. The theological work known as the Memphite Theology presented creation as a mental and verbal act of Ptah which placed intellect at the foundation of existence. Kings associated themselves with Ptah to legitimize their construction projects and authority.

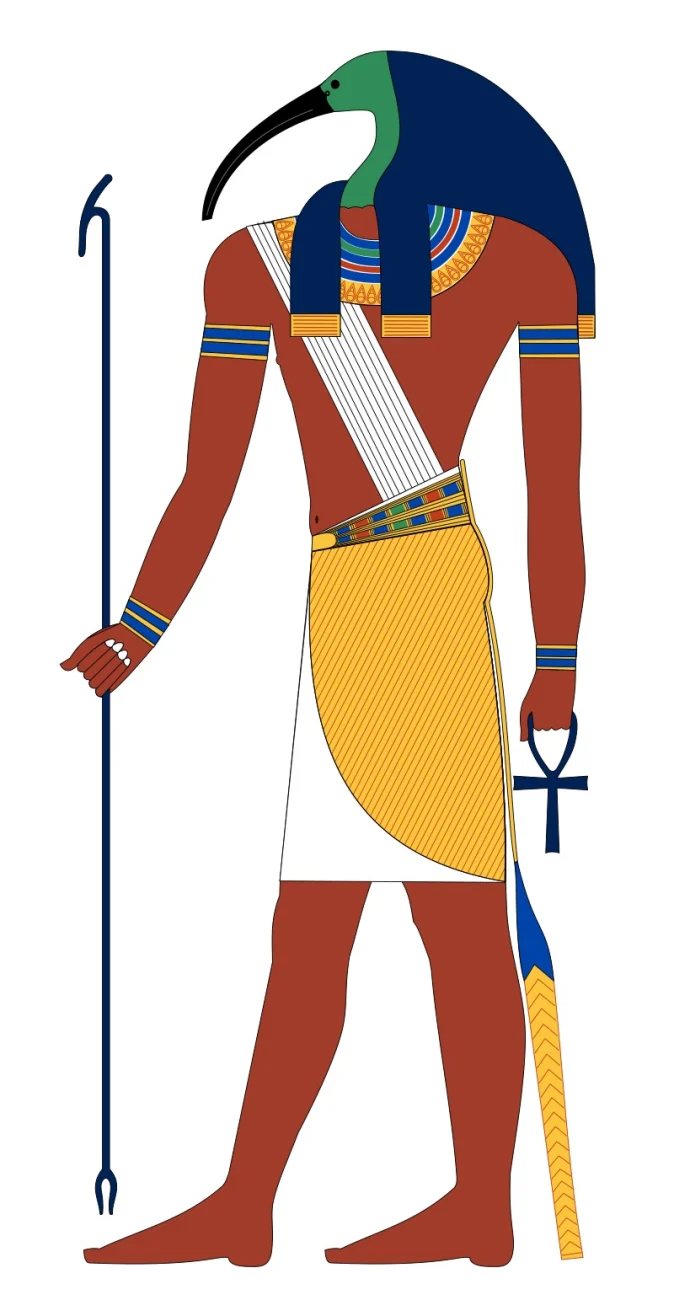

Thoth

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlThoth governed writing, calculation, and the regulation of time. Depicted as an ibis headed man or a baboon he recorded the verdicts of the divine court and measured the heavens. His lunar aspects balanced the solar power of Ra and maintained the calendar.

Hermopolis was his principal city where scholars and scribes honored him as master of hieroglyphs and divine books. In funerary texts Thoth stood at the scales to record the weight of the heart against the feather of maat. His libraries were believed to contain spells and knowledge that sustained temples and royal administration.

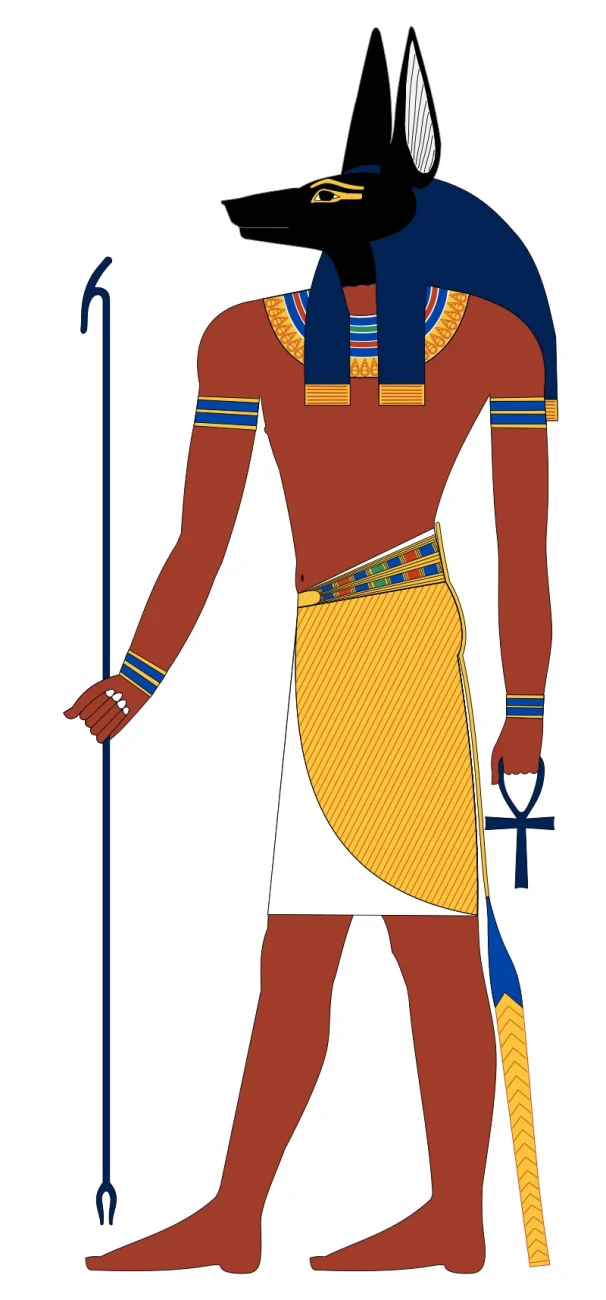

Anubis

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlAnubis guided the dead and protected mummification. With a jackal head he watched over cemeteries and ensured proper rites were performed. He invented embalming in myth and wrapped the body of Osiris which established the pattern for all funerary practice.

His shrines appeared in necropolises across Egypt including Saqqara and Thebes. Priests wearing jackal masks conducted processions and guarded the opening of the mouth ceremony that restored senses to the deceased. Amulets bearing his image were placed among bandages to secure safe passage through the gates of the underworld.

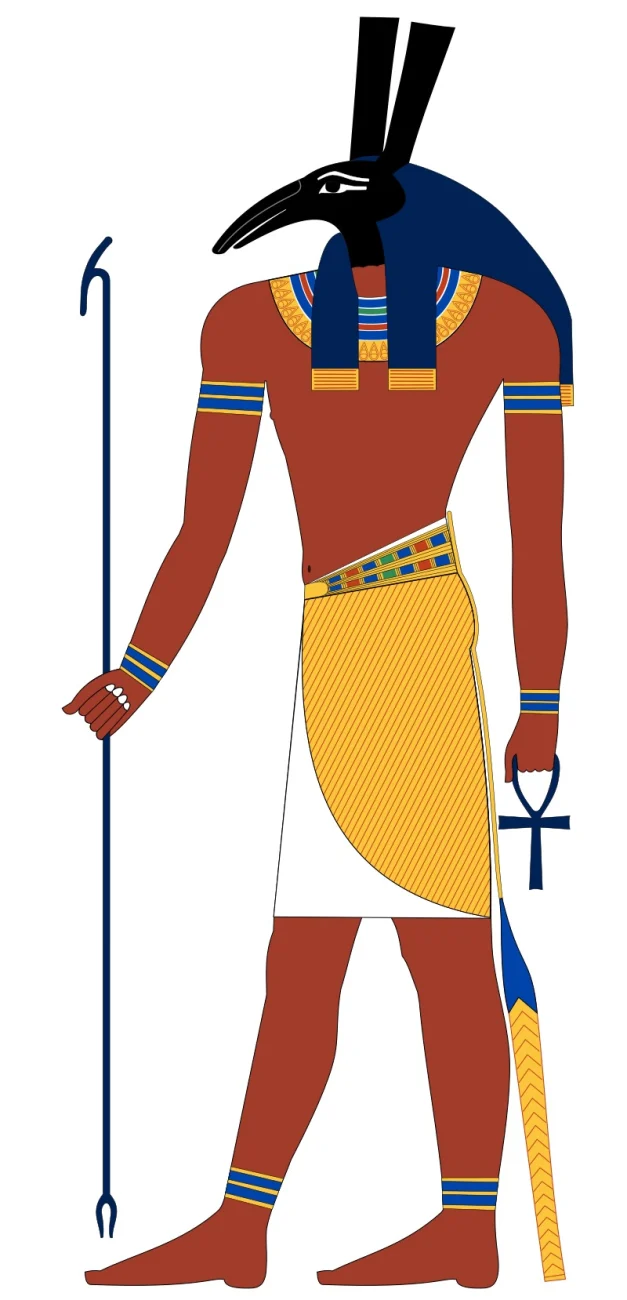

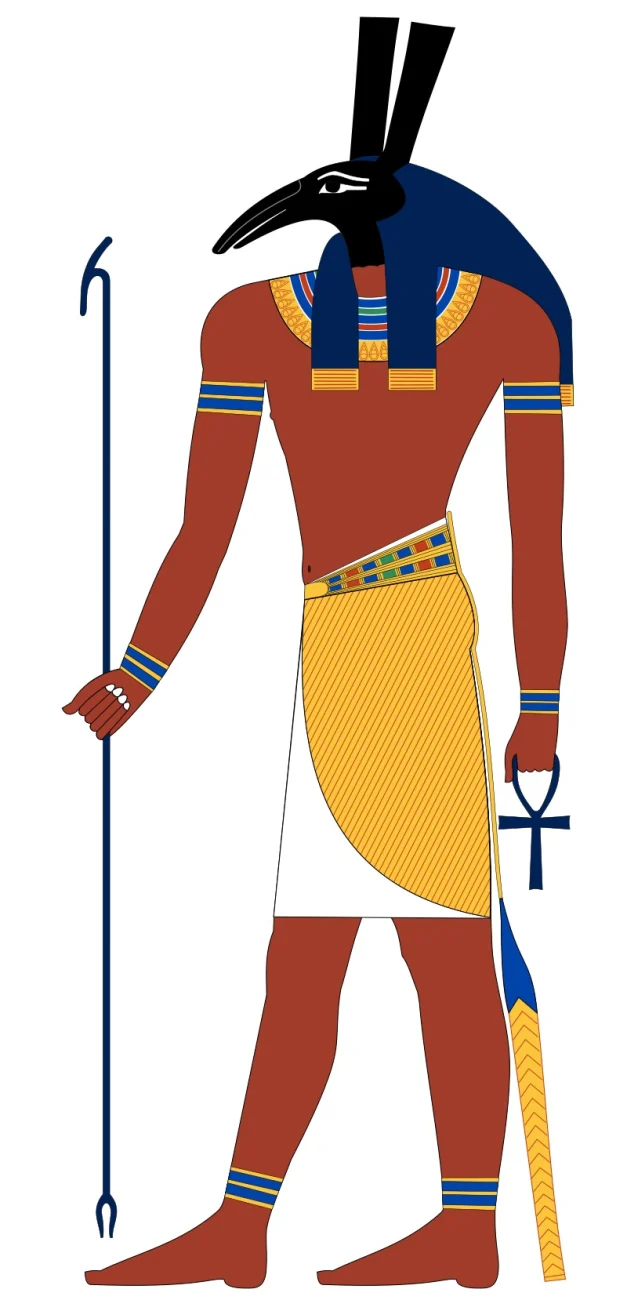

Set

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlSet ruled over desert storms and foreign lands and represented necessary chaos within the cosmic balance. He was shown with the enigmatic Set animal featuring a curved snout and forked tail. In early periods he protected the sun god on the nightly voyage and was honored in oases and border regions.

Over time myths emphasized his conflict with Horus for the throne of Egypt and his slaying of the serpent Apophis during solar battles. Kings of the Nineteenth Dynasty used his name and built temples in his honor at places like Avaris and Sepermeru. Military associations made Set a patron for strength in frontier campaigns.

Horus

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlHorus embodied kingship and the sky and appeared as a falcon or a man with a falcon head. His eyes represented the sun and the moon and his throne name formed part of royal titulary. Temples across Egypt depicted him standing upon crocodiles while grasping dangerous animals which signaled control over chaos.

The story cycle known as the Contendings of Horus and Set narrated legal and physical trials over succession. At Edfu a major temple preserved detailed ritual scenes that established the king as the earthly Horus. Coronation ceremonies drew from these traditions to connect each ruler with divine authority.

Isis

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlIsis was a master of magic, healing, and royal protection and served as the archetypal mother and queen. She gathered the scattered body of Osiris and used spells to conceive Horus which restored the royal line. Her headdress often featured the throne sign or later the sun disk between cow horns.

Her worship expanded beyond Egypt into the Mediterranean with temples in places like Philae, Delos, and Rome. Priests conducted mysteries that promised aid in this life and the next and sailors invoked her for safe travel. In late antiquity her cult remained influential due to promises of personal salvation and powerful ritual knowledge.

Osiris

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlOsiris governed the afterlife, resurrection, and agricultural renewal. He was shown as a mummified king holding crook and flail which signified rulership and care of the land. His myth explained the cycle of death and rebirth through his murder by Set and revival by Isis.

Abydos was his principal cult center where processions reenacted episodes of his story. Pilgrims left stelae to join themselves symbolically with his eternal life. Judges in the underworld operated under his authority and successful souls hoped to dwell in his realm known as the Field of Reeds.

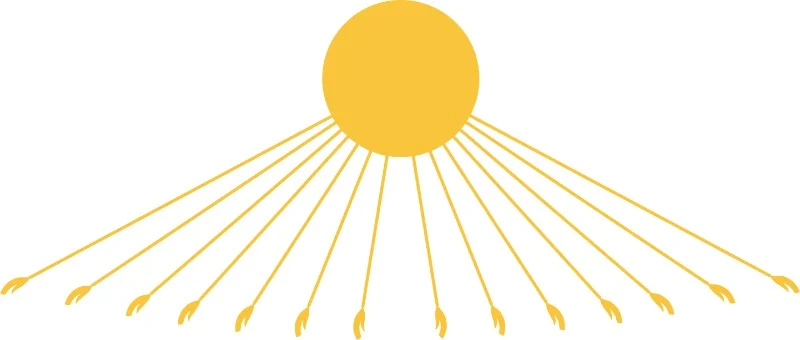

Aten

AtonX

AtonXAten represented the visible disk of the sun and the life giving rays that touched the earth. In the Amarna period worship centered on Aten as supreme without rival which shifted focus from traditional temples to open courtyards under sunlight. Art showed rays ending in hands that offered the ankh to the royal family.

A new capital at Akhetaten supported this system with hymns that praised the daily renewal of light. After the period ended the priesthood returned to the broader pantheon yet the theological emphasis on direct solar vitality remained a significant experiment. Aten’s prominence demonstrated how royal policy could redefine divine power for a time.

Amun

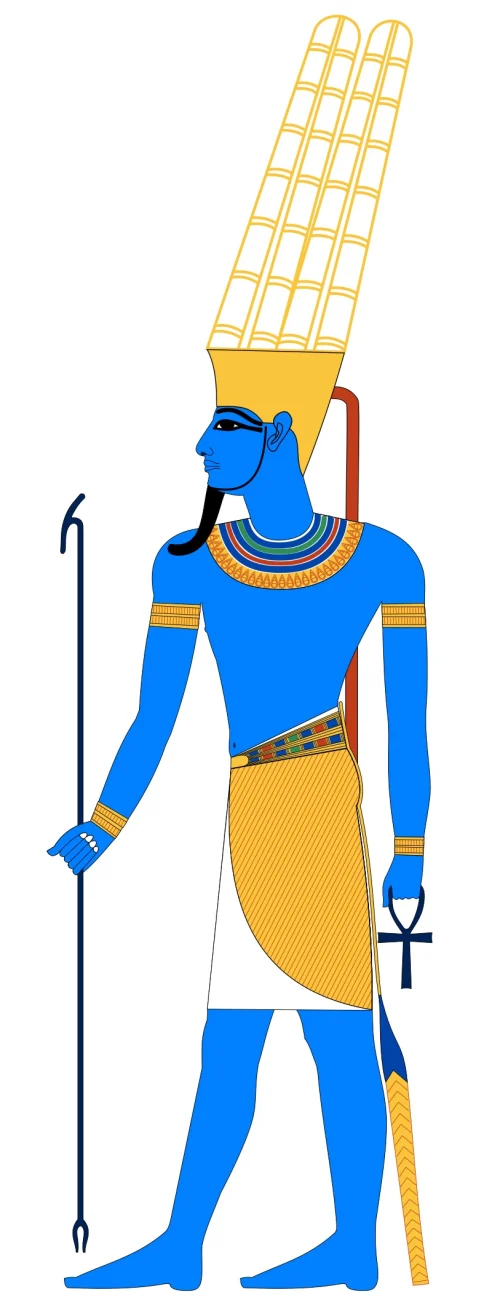

FDRMRZUSA

FDRMRZUSA Amun began as a local god of Thebes and rose to national prominence as hidden lord of wind and air. When combined with Ra he embodied both the unseen and the manifest aspects of divinity. His plumed crown and association with rams symbolized vigor and kingship.

Karnak Temple formed the heart of his worship where massive pylons and sacred lakes hosted grand festivals. The Opet Festival linked Amun with royal renewal as statues traveled from Karnak to Luxor. State oracles issued in his name guided political decisions which tied temple wealth to national authority.

Ra

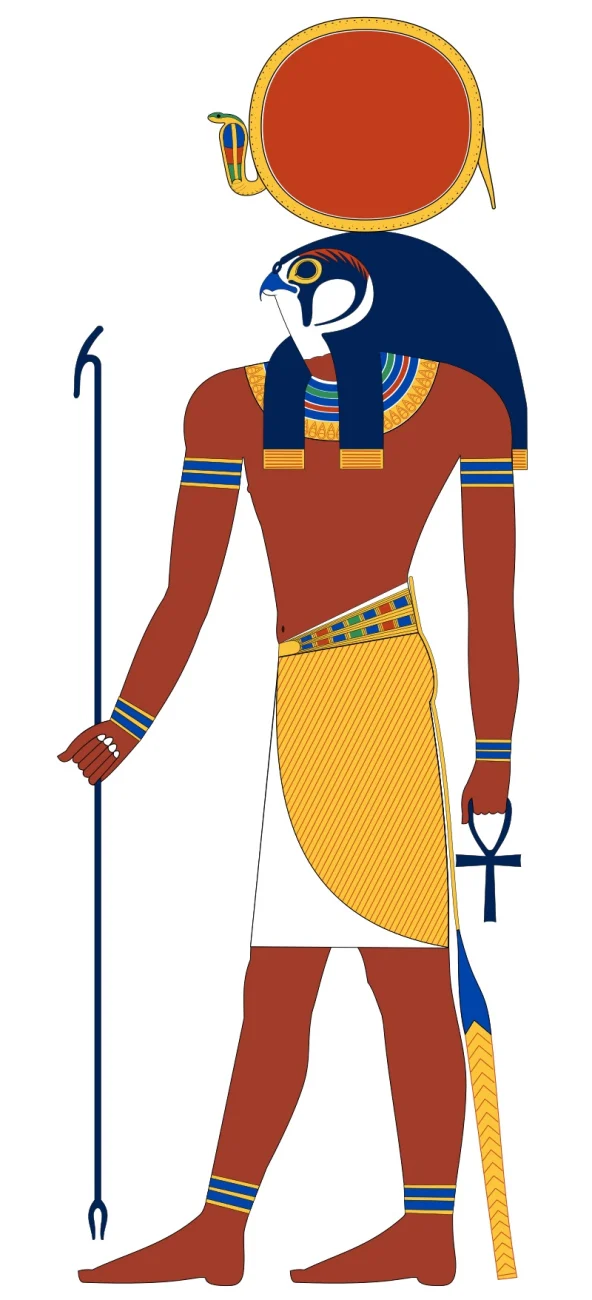

Jeff Dahl

Jeff DahlRa was the sun god who created and sustained the world through his daily journey across the sky and through the underworld. He appeared as a falcon headed man with a sun disk or as a scarab at dawn and an aged creator at dusk. His barque traveled the night waters where he defeated the serpent Apophis to ensure sunrise.

Heliopolis served as a key center where the Ennead genealogy placed Ra at the head of a family of gods. Pharaohs called themselves sons of Ra and aligned their rule with his cycle of renewal. Temples across Egypt oriented rituals to support his voyage so that light and order would return each morning.

Share which gods you think should make this list in the comments.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·